Lefty

Lefty was a racist skinhead; she beat up gays and spewed antisemitic bile. She was also Black, and a lesbian. Now that she's gone, the only question is: Why did I like her?

In the greenish shadows beneath the streetlamp, it was hard to make out details.

But there was definitely someone standing by my Vespa scooter. Someone big. At the sound of my footsteps, the figure turned around: shaved head, dark bomber jacket, and laced-up Doc Martens. My palms suddenly felt damp. He was a skinhead and I was a mod, kitted out in a vintage thrift-store suit and an old-style army parka. And I was quite possibly about to get my ass kicked.

As we drew nearer one another, I saw how much both heavier and taller than me he was—by several inches and several dozen pounds. Then, as he stepped forward and the lamplight finally illuminated his face, I saw that he was Black. And that he was a she.

“Nice scooter,” she said. “Is it yours?”

“Uh…yeah.” I felt slightly queasy.

“It’s cool,” she said. Her mouth was set in a slight grin, and in the darkness, amplified by my apprehension, its meaning was impossible to interpret. Then, still smiling that cryptic smile, she said: “I’m Lefty.”

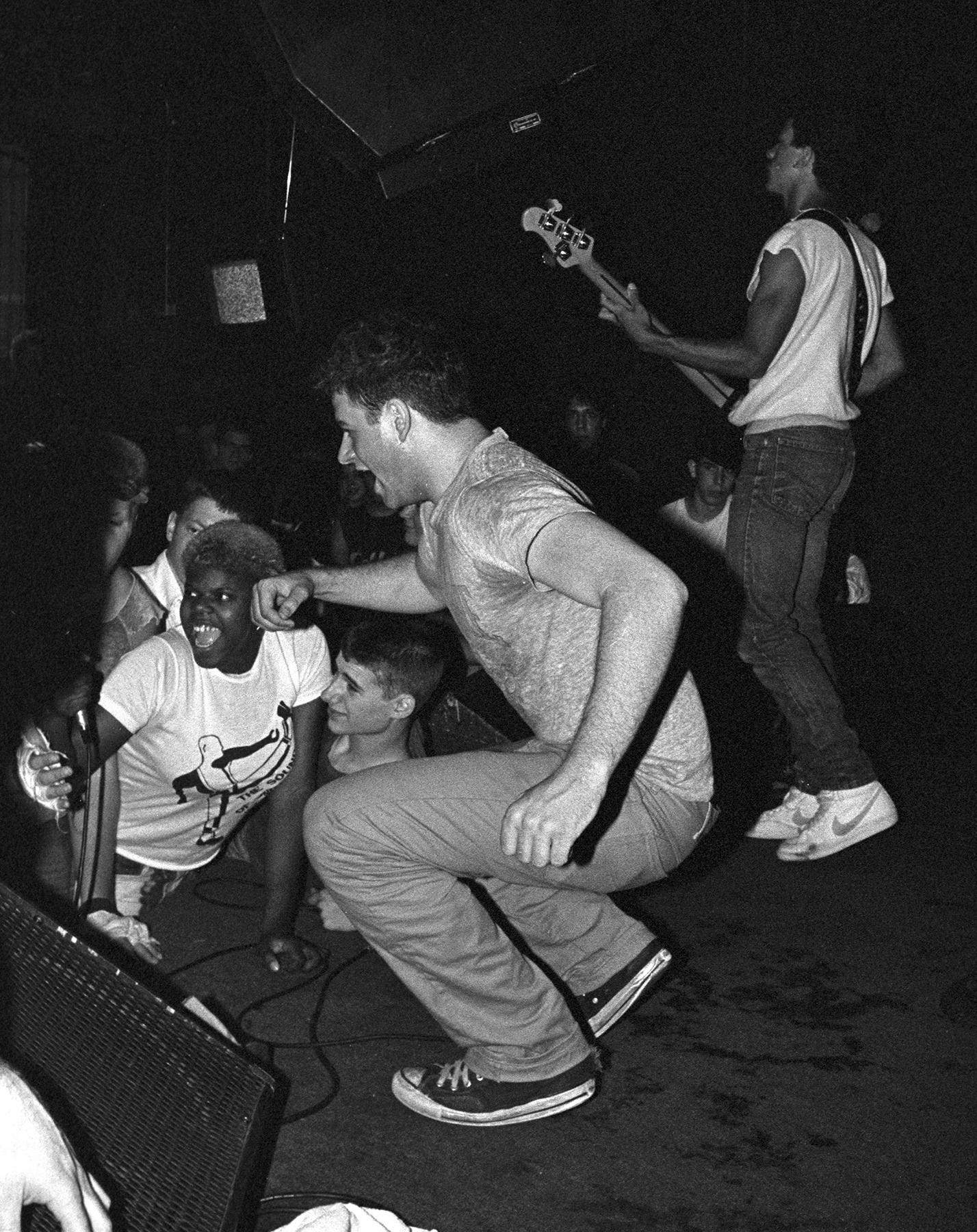

It was early 1986; I’d just turned 15. Over the coming years I’d learn more about Lefty, though everything I did left me wondering how much I really knew. Lefty seemed to be involved in every instance of bad behavior in the D.C. punk scene, and her name was known up and down the Eastern Seaboard. Her trademark—besides her penchant for random violence—was a camouflage-painted pickup truck. Flanked by an ever-replenishing font of young, white male skinheads, Lefty would break up parties, engage in petty theft, and generally make herself loathed. At one show, she taunted Danny Ingram—drummer with The Untouchables, Youth Brigade, and countless other punk and indie bands—for his Jewishness.

Which brings me to my own, complicated feelings about Lefty. I’m Jewish, and I deplore violence. I hated skinheads, and I never found anything the slightest bit redeeming about what Lefty did. Which is why I’m surprised to find—a few weeks after learning of her death—that what I feel is grief. I actually liked her, and I think she liked me, too.

When I entered the D.C. punk scene, a fully formed world unfolded around me.

Life became theater, and here amongst the rockers, bike messengers, street poets and queer performance artists I felt like I’d found a secret city. Beneath Washington’s hustle and grind was a world of tribes and allegiances, and I was certain I’d never go back.

I became a student of details. Did white laces on Doc Martens really mean the wearer was a white supremacist? Or just that they were straightedge? The color of suspenders, the slightest variations in hairstyle or lapel size all held significance invisible to the uninitiated—sometimes to the wearers themselves.

As my perspective on the outside world changed, so too did my interior one. The mod soundtrack—The Jam, the early Who and Kinks and Small Faces—touched me on a deep level, and my teenaged reinvention gave me a sense of belonging I’d been craving. Never mind that I was aping a British working-class subculture; dressing like it was 1965 made me feel different. In a uniform, I felt somehow more unique.

But if mods were the butterflies of the punk scene, skinheads were the murder hornets: Cocky, unpredictable, violent. In retrospect, it’s easy to see why Lefty became one. I can’t know for sure, but I imagine being a big, dark-skinned girl—even in majority-Black D.C.—was a heavier burden than I’ll ever know.

But if uniforms are designed to flatten our differences, they can have the opposite effect, too. If Lefty imagined that being a skinhead erased her most visible traits, they also heightened them. The lone Black girl in a sea of hard, white male faces, Lefty could only ever be an anomaly.

And of course, there were the less visible traits. It will not surprise you to learn that the young woman who delighted in violence towards homosexuals was herself a closeted lesbian. Surrounded by her crew of young, stridently straight boys, Lefty deflected her shame in the worst of all possible ways, prowling Dupont Circle—then Washington’s most openly gay neighborhood—to taunt and physically assault homosexuals.

Lefty also made life miserable for those who would otherwise have been her natural allies.

One former punk, who requested anonymity, received constant harassment from Lefty for being an out lesbian: “If I saw her hanging out with people I knew, I’d just keep going,” she recently wrote. “It was just way too unpleasant.”

Years later, the two had an unexpected encounter in a Washington gay bar. But if Lefty had finally embraced her sexuality, it was too late for her former target. “Lefty came sidling up to me in a cowboy hat, trying to make peace,” the former punk wrote. “I just turned around and left.”

Lefty was objectively awful. A quick scan of social media comments following her death reads like a police blotter: “She beat my boyfriend with a tire iron”—“she ripped the t-shirt off my back and set it on fire”—“she chased my friends into the road and threw rocks at us.”

The question, for me at least, is why I liked her. Maybe it was because her tenderness was plain to see, at least for those attuned to such things. Conflict-avoidant, hesitant, and Jewish to boot, I often felt like an imposter in the punk scene. I never perpetrated acts of violence on others, but there were many times I wished I could. Had I been able, would I have ended up like her?

My mod phase lasted a couple of years, ceding to others—‘60s garage, ‘70s punk—in a self-consciously historical progression.

I took my cues in music and fashion from all of them, but over time they blended into an idiosyncratic lexicon I could finally call my own. It was only after I’d shed my uniform that I began to embrace the parts of myself I’d tried to exile. My life got better, and I took things less personally. And once in a very great while I’d wonder what’d happened to Lefty.

On a visit back to the District, years after I’d moved away, I found myself back in Georgetown, the neighborhood that—decades before—was the site of brawls between punks and skinheads. Now I wasn’t anything. Not a mod; not a punk; just some guy. I was passing the CVS on Wisconsin Avenue when a woman walked out and fell into step next to me.

“Hey,” said a surprisingly soft voice. I turned to face the speaker, but I didn’t recognize her. In her dorky polyester vest, she was just an anonymous drugstore clerk. Then, seeing my blank expression, she said: “It’s Kendall.”

I’d forgotten that was Lefty’s given name—Kendall Hall. The fear I’d felt at our first meeting was gone. In its place was a tiny spark of joy: I was glad to be recognized. Having swapped uniforms, Kendall seemed sweet, even slightly fragile. We chatted for a few minutes, then said our goodbyes. I never saw her again.

I know, through our few mutual friends, that Lefty’s last years weren’t easy. She worked at UPS, apparently losing her job after losing her temper and trashing her truck. She was homeless for a while, then found an apartment through a charitable organization.

This January, a case worker drove her to a grocery store and waited outside. Soon an ambulance pulled up; while shopping, Lefty had suffered a stroke. Despite surgery to alleviate the pressure in her brain, she never regained consciousness.

By the slimmest of chances, Lefty’s case worker managed to contact one of Lefty’s few known associates, a woman named Carolyn Fischer. Their friendship was even unlikelier than mine. One night in the early ‘80s, Fischer and a female friend were hanging out in the alley behind the old 9:30 Club when Lefty approached and demanded the woman’s leather jacket.

When she refused, Lefty took out a knife and slashed her eyebrow, sending a freshet of blood down her face. Fischer, despite her comically slight stature (5’2” and 110 pounds), screamed at Lefty to back off; she remembers having to crane her neck upwards to look up into the far larger woman’s eyes.

Maybe it says something about the size of the D.C. scene—one in which everyone seemed to know everyone, at least by name—and maybe it says something about Lefty, but Fischer became friendly with her, though she never condoned the violence she perpetrated.

After Lefty’s case worker found her, Fischer visited her former tormentor in the ICU. That evening, after a priest administered the last rites, Lefty was taken off her ventilator. She passed in peace, with Fischer at her side, a couple of days later. She’d turned 60 roughly a week before.

In her last years, Kendall expressed deep remorse for her actions. According to Fischer:

“She denounced all the racist crap she supported back then. It was evident to me back in the ‘80s that her public persona was a facade to hid and protect the kind, caring, vulnerable girl inside. Not many got the chance to see that part of her but to me that was the real Lefty—a complicated person who felt a duty to protect others.”

Kendall’s public memorial was March 23rd, 2024. Fittingly, it was held in Dupont Circle, where she once tormented people no different from her but for their courage. There’s no way to forgive her—not that it’s up to me, anyway. But for a brief flicker of a moment, I saw who Kendall really was and—while I’m glad I never became like her—I cared for her, more than I knew. I hope she’s at peace.

Interested in more dispatches from the fringe? Consider becoming a paid subscriber! It’s a great way to support my work, help me to craft more great writing, and support independent creatives such as myself.

A friend of mine messaged me this evening, " Do you remember Lefty?" My reply, "Yup, how could you forget?" And how could you? She was such an icon of that DC, those times, a deep conundrum. Every encounter with her felt like barely eluded violence for sheer proximity. Thank you for this tender tribute. I never could understand but it had to be such a relentless rejection of herself that drove her. RIP Kendall.

RIP Lefty. She stuck up for me one time when some gross dude was following me and pestering me near Dupont Circle. It was late, streets were mostly empty, and I was just leaving a shift at Cafe Rabelais, where I worked. This was an odd contrast to the many times I had witnessed her starting fights and bullying pretty much everyone (sometimes she even turned against those white skinhead boys who idolized her).

As a not yet out gay person myself in the mid ‘80’s, she always was intriguing to me because she was so very butch; I was drawn to her and felt a kinship. But she was so unpredictable. It never felt safe to try to befriend her.

I’m glad to know that someone who had history w her was by her side in her final hours.

I wish I could make it to her memorial today. Thanks for sharing this, Seth. I also sent this to my little brother, who she frequently beat the shit out of and stole things from 😂.